The Other Source: Where Does Plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch Come From?

Back to updates-

Our new study published today in Scientific Reports reveals 75% to 86% of plastic debris in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) originates from fishing activities at sea.

-

Plastic emissions from rivers remain the main source of plastic pollution from a global ocean perspective.

-

Plastic lost at sea has a higher chance of accumulating offshore than plastic emitted from rivers, leading to high concentrations of fishing-related debris in the GPGP.

-

New findings confirm the oceanic garbage patches cannot be cleaned solely through river interception and highlight the potentially vital role of fishing and aquaculture in ridding the world’s oceans of plastic.

The Ocean Cleanup has published its latest findings on the composition, origins, and age of plastic debris accumulating in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP). These findings add to our understanding of the plastic pollution problem, helping us refine our cleaning strategy and gain insight into the origins of this plastic.

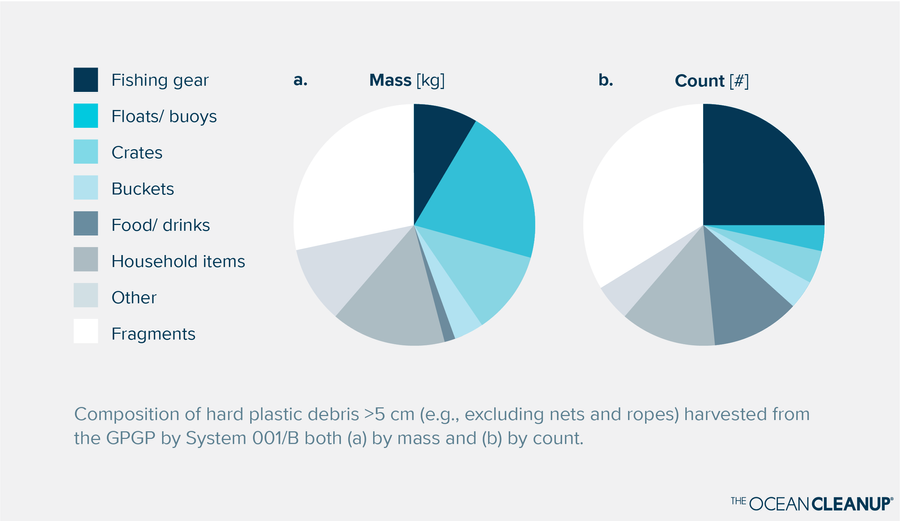

Our previous research has shown that almost half of the plastic mass in the GPGP is comprised of fishing nets and ropes (fibrous plastics used, for example, to make our The Ocean Cleanup sunglasses), with the remainder largely composed of hard plastic objects and small fragments. While the provenance of fishing nets is obvious, the origins of the other plastics in the GPGP have — until now — remained unclear.

COMPOSITION AND AGE OF GPGP PLASTICS

Data on plastic debris afloat at sea has typically been based on data collected through small-scale surface trawls, initially developed to collect plankton. Due to their small size, these trawls typically collect small plastic fragments. It is difficult to trace the origins of these small fragments, limiting their usefulness in determining where GPGP plastic comes from.

Larger plastic objects, on the other hand, can sometimes carry clues that can help clarify their age, as well as their source and geographical origin. Such items, however, have only rarely been collected by seagoing researchers. Instead, they are mostly quantified using remote sensing techniques.

To address this gap in the data, in 2019, System 001/B, an early iteration of our cleanup technology, retrieved over 6000 hard plastic debris items (larger than 5 cm) from the GPGP, providing our scientists with a unique opportunity to study larger objects not studied by previous research efforts. Each item was sorted into predefined item categories and inspected individually for evidence of country of origin (evidence may include language or text on the object, company name, brand, logo, or other identifying text such as an address or telephone number, etc.) and date of production.

This comprehensive analysis revealed that roughly a third of the items were unidentifiable fragments. The other two-thirds was dominated by objects typically used in fishing, such as floats, buoys, crates, buckets, baskets, containers, drums, jerry cans, fish boxes, and eel traps.

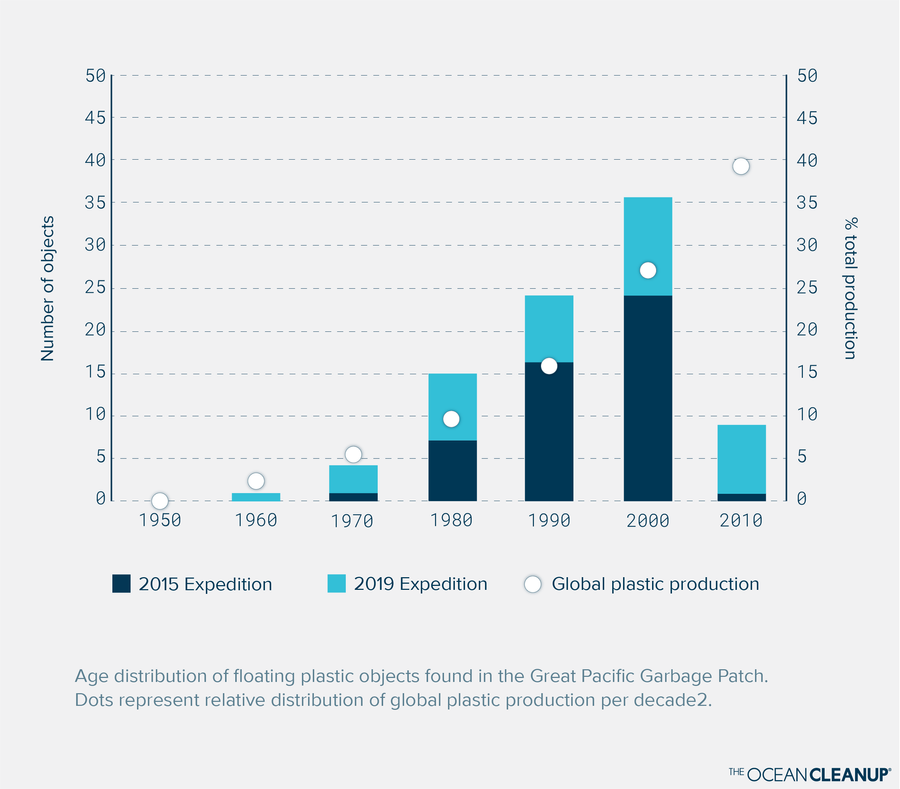

Nearly half (49%) of plastic objects which could be dated were produced in the 20th century, with the oldest identified item being a buoy dating from 1966. This distribution is in line with our previous research showing significant occurrence of decades-old objects in the GPGP and re-emphasizes that the plastic in these garbage patches persists and can cause harm for lengthy periods, continually degrading into microplastics and becoming increasingly difficult to remove. In short, these results underline the urgent need to clean the GPGP; no matter what actions are taken to prevent riverine plastic emissions, the GPGP will persist and its content will continue to beach on remote islands, such as the Hawaiian Archipelago, and fragment into microplastics that will eventually sink to the seabed.

COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN AND FISHERIES

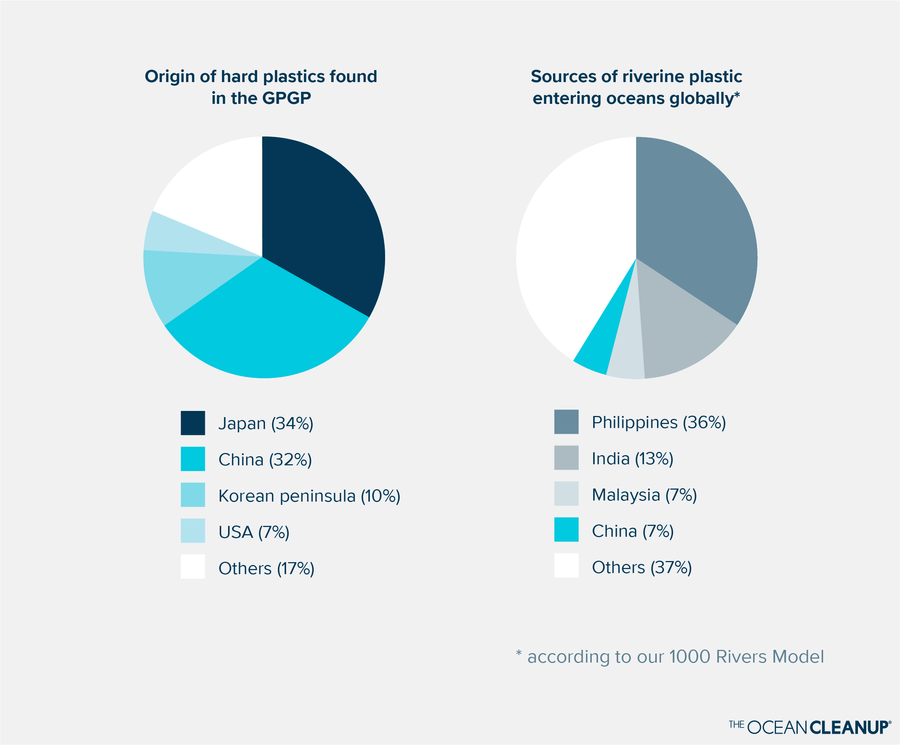

The primary countries/regions of origin identified on the items were Japan (34%), China (32%), the Korean peninsula (10%), and the USA (7%). Perhaps contrary to expectations, however, other countries at the rim of the North Pacific Ocean with high predicted riverine plastic emissions (such as the Philippines, for example) were not well represented in the plastic items collected from the GPGP.

The presence of high quantities of plastic from China, Japan, the Korean peninsula and the USA in the GPGP may not be entirely intuitive; most of these places are not recognized as major sources for riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. However, they do carry out the majority of industrialized fishing activities in the GPGP region.

Our scientists were intrigued by the apparent mismatch between the well-reported dominance of land-based emissions of plastic into the ocean on one hand, and the large quantity of fishing-related plastics in the GPGP on the other. If most floating plastic in the global ocean comes from rivers (i.e., from land, not from offshore fishing), why is the GPGP largely full of plastics from this other source – namely, from fishing activities?

Our research proceeded to identify the pathways which lead plastic to accumulate in the GPGP. To do this, they conducted a series of global numerical model simulations to test various scenarios, analyzing plastic emissions both from land and from fishing activities at sea. In simple terms, the models release virtual plastic particles into the ocean (either from rivers or from fishing vessels) and simulate the dispersal of these virtual particles across the ocean surface using available data on sea currents and wind.

These plastic dispersal models are useful tools to study the transport of floating marine debris. The models record the country of origin (for particles simulated entering the ocean from rivers) or the flag of the fishing vessel (for particles simulated entering the ocean from fishing vessels at sea). This allows us to trace the country of origin of each virtual plastic particle accumulating in the GPGP; a huge step forward in our understanding of precisely what plastics make up the GPGP, and where they come from.

DOMINANT CONTRIBUTORS TO THE GPGP

The correlations between the modelled origins of plastic and the origins observed in the field were generally higher with the fishing source scenario than with any land-based scenario. Virtual model particles accumulating in the GPGP were predominantly identified as originating from Japan, China, the Korean peninsula and the USA, consistent with the findings from the compositional analyses. This provides strong evidence that a large proportion of floating hard plastics (i.e., not only the fishing nets themselves) in the GPGP derive from fishing activities at sea, and were not emitted directly from land.

The fishing source scenario also gave insights into the dominant fishing techniques that contribute to plastic in the GPGP. Trawler activity made up 48% of fishing activities that contributed to model particles found in the GPGP, while fixed gear and drifting longlines totaled 18% and 14% respectively. For 16% of modeled fishing activities contributing to model particle emissions, the technique was unidentified and may have been representative of any one of these three gear categories.

As such, trawlers, fixed gear, and drifting longlines accounted for more than 95% of identified fishing activities that may account for emissions of floating plastic debris into the GPGP. Trawling and fixed gear activities contributing to the GPGP generally occurred near the Asian and North American continental shelves, while drifting longlines activities were distributed throughout the oceanic zone of the whole North Pacific Ocean.

Lastly, the models help us understand why land-based input scenarios do not accurately reflect the identified origins of floating GPGP plastic. Floating plastics emitted from rivers have a much greater chance of rapidly returning to land than plastic debris emitted by fishing activities at sea; if the plastic is emitted closer to the shore, it is more likely to find its way back to the shore. Virtual plastic particles released from rivers generally spent a lot of time near the shoreline, with a high chance of beaching close to the river mouth.

Modeled particles released by fishing, on the other hand, often spend very little time near a coastline, sometimes not encountering any land at all during the seven-year simulation period. Depending on the assumed probability of beaching, our models suggest that floating plastic debris emitted from fishing activities is potentially two to ten times more likely to reach the GPGP than plastics originating from rivers. This explains why rivers, while being a much larger source of plastic to the world’s oceans than fishing activity, only makes up a small part of the plastic accumulated in the GPGP. Clearly, these findings have significance for cleanup strategies, and for those undertaking fishing activities in the Pacific.

Additionally, floating plastic items entering the oceans from rivers mostly differ from the type of hard plastic debris found in the GPGP, which are largely thick, positively buoyant plastics made of polyethylene and polypropylene. These plastics represented less than 15% of observed plastics flowing at the surface of European and Asian rivers, suggesting that the rest either rapidly fragments into smaller particles, beaches onto coastlines, or sinks to the bottom of the coastal ocean (or a combination thereof).

HOW DOES THIS RESEARCH CONTRIBUTE TO CLEANER OCEANS?

Fully cleaning our oceans of plastic requires that we first know where and how plastic enters the ocean, and what happens to it once it is there. This knowledge is particularly relevant for floating plastic objects that can be transported over vast distances at sea, creating a transboundary problem, where the regions or nations suffering most impact are often not the original polluters.

Litter monitoring programs and local cleanup efforts are useful tools to derive composition, abundance, sources, and origins of plastic debris. These programs are mostly focused on debris collected from coastal environments, where the composition of accumulated plastic waste differs by location. Negatively buoyant plastics are generally found closer to land-based sources, while positively buoyant plastics dominate remote areas. Plastic debris afloat at sea, however, remains less well-characterized, and this is where our offshore cleanup activities can continue to provide valuable data and insights.

In order to create effective and efficient mitigation strategies against ocean plastic pollution, it is necessary to discover the precise entry points of plastic debris persisting in the offshore waters, where that plastic is produced, and what practices (commercial, cultural, or industrial) are contributing to its accumulation at sea. Monitoring the composition of our offshore catch further provides the observational baseline to evaluate the efficiency of various mitigation measures on the accumulation of specific type of debris at the ocean surface.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR OUR CLEANUP STRATEGY?

At The Ocean Cleanup, our mission is to rid the world’s oceans of plastic. These results reinforce our two-pronged approach to achieving this mission: stemming plastic in rivers and removing legacy pollution in oceans. While plastic accumulating in the GPGP itself mostly comes from marine-based activities, it is land-based emissions that contribute the majority of plastic in the oceans globally. Thus, by intercepting plastic in rivers, we can stop plastic from entering the ocean in the first place, and largely eliminate plastic pollution in the world’s coastal waters.

However, this research confirms that cleaning up the GPGP and keeping it clean will require more. The identification of this other source of plastic to the GPGP reveals a simple truth for our cleaning strategy: while it remains essential to continue intercepting riverine plastic and cleaning up the legacy plastic in order to clean the global ocean, the GPGP itself requires an additional step. To sustainably clean the GPGP, the other source – fishing activities – must also be addressed.

Whether The Ocean Cleanup can play a role in the prevention of fishing gear losses is to be seen, based on further research. In any case, we hope this study provides valuable observational data for other organizations working to tackle this other source of ocean plastics. Identifying the provenance of ocean plastic will also help formulate strategies and better inform states in addressing the ocean plastic pollution issue, including in the context of the ongoing negotiation of a new United Nations Plastics Treaty.