The Quest to Find the Missing Plastic

Back to updates- Plastic in the ocean garbage patches is persistent, according to new study

- Nearly half the plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is from the 1990s and older

- Projections show the mass of ocean plastic could quadruple by mid-century, if not intervened

- Even if plastic stops entering the ocean, microplastic contamination will double due to the fragmentation of legacy pollution

- Solving the plastic pollution problem, therefore, requires a global effort for both source reduction and active cleanup

For the last five years, researchers at The Ocean Cleanup have been working to understand the scope of ocean plastic pollution in order to help the organization effectively design technology to solve this problem. In 2018, we reported that 80,000 metric tons of plastic were currently floating in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a figure four to sixteen times larger than previously estimated. We explained this increase by using robust methods to quantify the myriad of size classes composing plastic pollution, ranging from huge ghost nets to miniscule microplastics.

Extrapolated at a global scale using numerical models, we projected several hundred thousand metric tons currently floating at the ocean surface. Although these figures are alarming, they conflict with current global estimates of plastic inputs into the ocean (Jambeck 2015, Lebreton 2017), which predict several million metric tons enter the oceans every year. With plastic use swiftly rising in recent decades, we should be finding dozens of million metric tons of plastic on the ocean surface by now. But, we don’t. Which leads us to ask: where is the ‘missing plastic’?

THE PLASTIC SMOG HYPOTHESIS

The commonly accepted understanding is that floating plastic pollution doesn’t persist at the surface; rather, it is assumed its ultimate fate could be at the bottom of the ocean. The idea is that, just like a smog cloud over a city, the small particles descend into deeper waters as they break down (Eriksen, et al. 2016). According to the smog hypothesis, if we were to stop plastic inputs into the ocean today, the majority of floating plastic debris would degrade and settle below the ocean surface layer, in less than a few years (Koelmans 2017).

The idea that plastic rapidly disperses like smog raises more contradictions, however. In the field, we still find perfectly intact Japanese objects, likely originating back from the 2011 tsunami. But, mostly, the plastic we bring back from our expeditions and cleanup test operations appears very old as well. Some plastic has been dated back to the 1970s, clearly making it difficult to accept that the majority of HDPE fragments we collect were perfectly intact plastic objects only a few years ago.

We know that the primary mechanism for plastic degradation is photo-oxidation. This occurs when plastic is in contact with oxygen and bombarded by photons. Yet, plastic floating in the oceans is mostly submerged, so it rarely encounters those conditions. In fact, plastic is better conserved when submerged in seawater rather than exposed to the open air (Andrady 2011).

To resolve these contradictions and quantify the smog of plastic, we chose to sample in deeper waters. We performed this sampling in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch by deploying sediment traps for twelve months below the surface. Later this year, we will retrieve these traps, which should provide further insights into potential fallout mechanisms in this region.

In the meantime, we went back to our desks and continued questioning the ocean plastic smog hypothesis. Using evidence collected in the field and numerical models for the dispersion of floating ocean plastic, we propose an alternative explanation for the missing plastic. This new theory on the fate of floating plastic objects has been presented to the rest of the scientific community in the manuscript “A global mass budget for positively buoyant macroplastic debris in the ocean,” which was published today in the journal Scientific Reports.

PLASTIC ARCHEOLOGY

It is extremely difficult to date ocean plastics with the available knowledge; there is no technology that will identify how long plastic has been floating in the ocean. The best way we found to estimate the age of plastic objects is to look at clues on the debris, such as labels, production dates, and organisms that have grown on floating objects.

Since we began exploring the North Pacific Ocean and collecting debris with our trawls, we have systematically documented this type of evidence on collected ocean plastics.

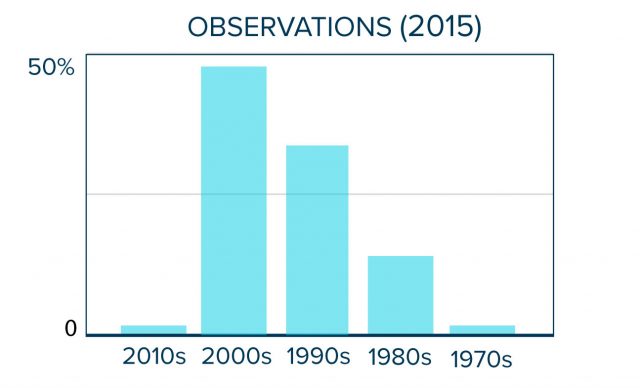

Of the 83,144 plastics pieces collected from the Mega Expedition larger than 0.5 cm, we identified fifty production dates labeled on plastic debris. Half of the debris with recognizable production dates were produced in the 70s, 80s, and 90s – making our oldest identified sample more than forty years old.

Having this understanding, we must then reconcile two seemingly paradoxical findings:

- The large difference between mass inputs and accumulated mass in subtropical gyres, suggesting rapid removal, and

- the significant occurrence of decades-old objects in these waters.

By creating a simple box model, we were able to predict the age of plastic populations in the marine environment. We found that, in order to satisfy the two conditions, the cause of the ‘missing plastic’ must affect the plastic prior to it reaching offshore waters. Subsequently, this points to coastal environments playing a major role in capturing and filtering ocean plastic debris.

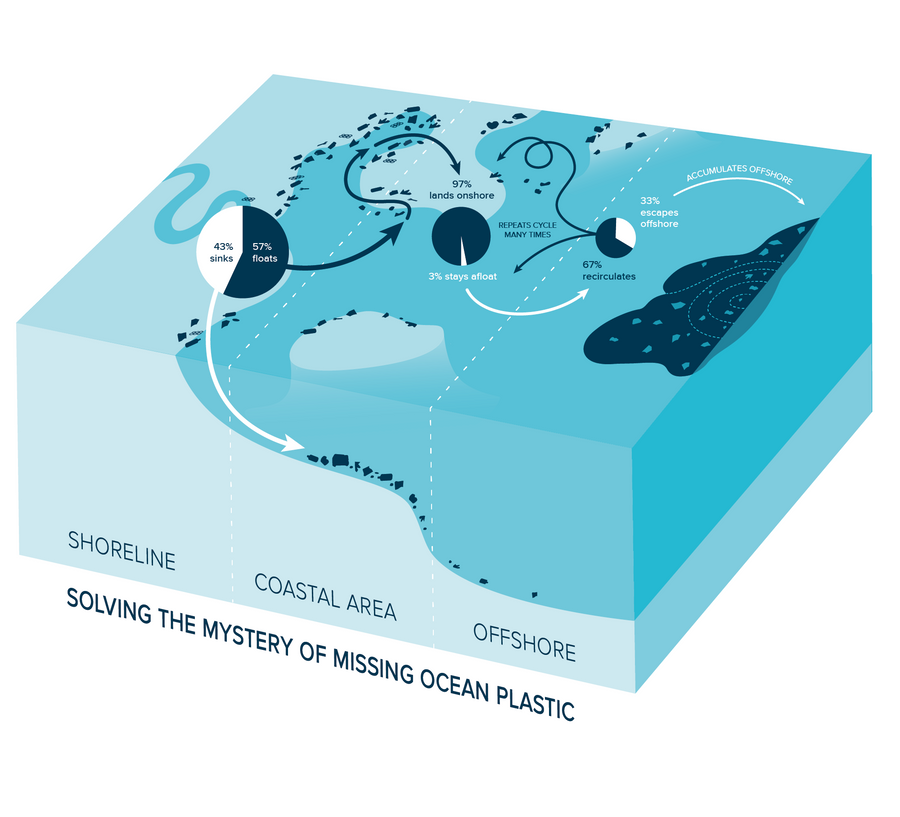

Our model simulations show that a large portion of plastic emitted from rivers likely returns to shore not long after being released. Beached plastic may be collected by humans or left to fragment in the coastal environment. Other accumulated beached plastics will be picked up by the waves and sent back to shore with the tide, possibly repeating this cycle numerous times over the years. A small fraction of the plastic that is retrieved by the waves and currents eventually escapes into the offshore environment.

These beaching cycles, which may be repeated for an unknown frequency depending on the distance of rivers to oceanic gyres, result in a significant delay between plastic release and representative accumulation offshore. Our model results suggest this delay could be in the order of several years to several decades. We argue that the missing floating plastic has not disappeared into a smog of invisible particles at the bottom of the sea, but rather is slowly degrading as it beaches or recirculates from coastal environments, eventually making its way to offshore waters.

This explanation has important implications as it suggests that (1) the persistence of ocean plastic pollution in offshore surface waters is much larger than previously anticipated (see supplement Modelling the age of ocean plastic populations), and (2) the trillions of microplastic fragments currently polluting offshore waters is mostly representative of the fragmentation of objects produced and discarded decades ago.

IMPLICATION FOR THE FUTURE OF THE OCEAN

In our study, we introduce the concept of plastic age and we try to understand the timescales relative to accumulation of floating plastic litter in offshore subtropical waters. Once we have found a coherent mass balance model, by matching global estimates as well as our field observations, we can look into the future. Our parameterized model allows us to predict future quantities of plastic in the ocean based on different emission scenarios.

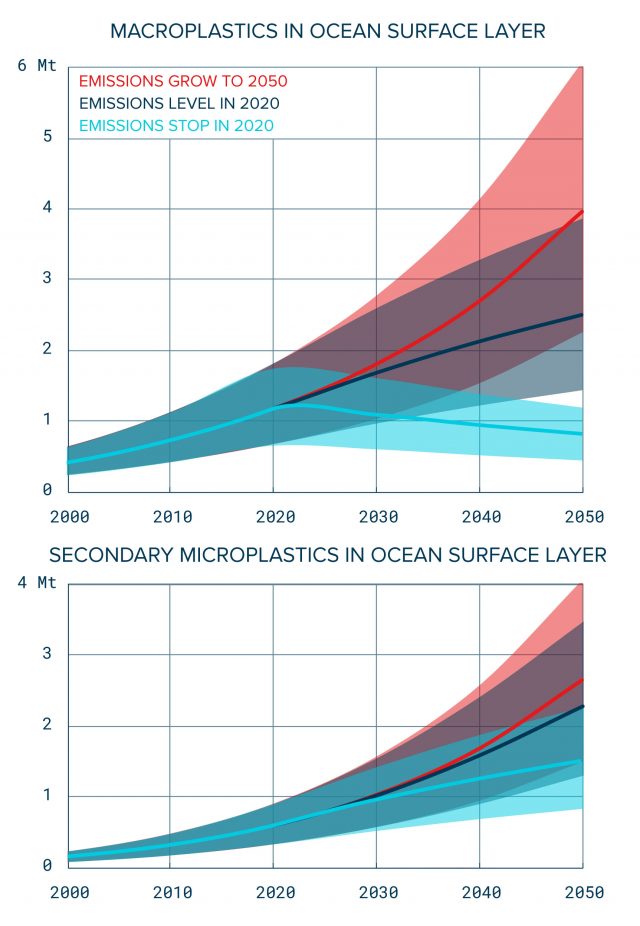

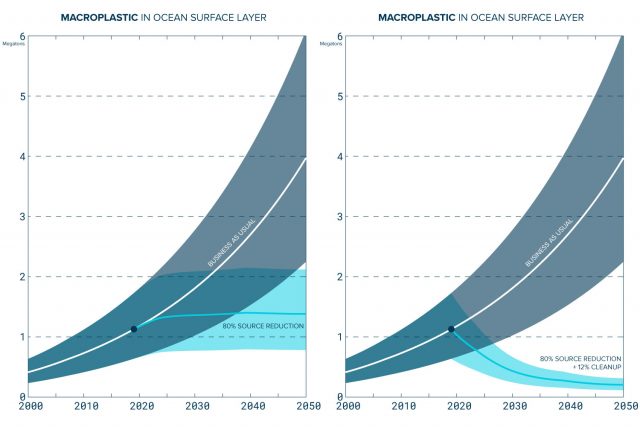

Here we investigated three possible futures for plastic emissions into the ocean:

- Business as usual scenario, where river emissions grow with global plastic demand

- Significant mitigation efforts implemented, by leveling sources to a constant value starting in 2020

- Drastic efforts are taken to cut sources down completely by 2020

Our model predicts under scenario (1), where no effort is given to mitigating river emissions, the quantities of buoyant macroplastics at the surface of the global ocean could quadruple by the year 2050. Under scenario (2), the mass of buoyant macroplastics on the global ocean surface and coastlines continues to increase, although at a slower rate due to the degradation of older objects into smaller particles. From now to mid-century, only scenario (3) shows a decrease of macroplastic mass at the surface of the ocean and global coastline. However, in this scenario, the mass of microplastics in the ocean would still more than double from 2020 levels, as material left in the environment is slowly fragmenting.

The results presented in this study are important because we see that mitigating plastic pollution in the global ocean will require the combination of both prevention and curative strategies. This conclusion can likely be applied to any natural environment from mountain to sea. If humanity today doesn’t want to leave the legacy of a continually increasing number of fragmenting plastics in seas, rivers, forests, and the soils of this planet, we should urgently be aiming to completely stop emissions and actively engage in cleanup operations on a global scale.

PREDICTING THE IMPACT OF DIFFERENT MITIGATION STRATEGIES

SUPPLEMENT: MODELLING THE AGE OF OCEAN PLASTIC

This box model representing the global marine environment is sectioned by (1) the shoreline, (2) coastal waters, and (3) offshore waters. We investigated the populations of macro-sized plastic objects in each compartment and their evolution over time. Plastic population is defined by its distribution of age from young to old, just like human population pyramids.

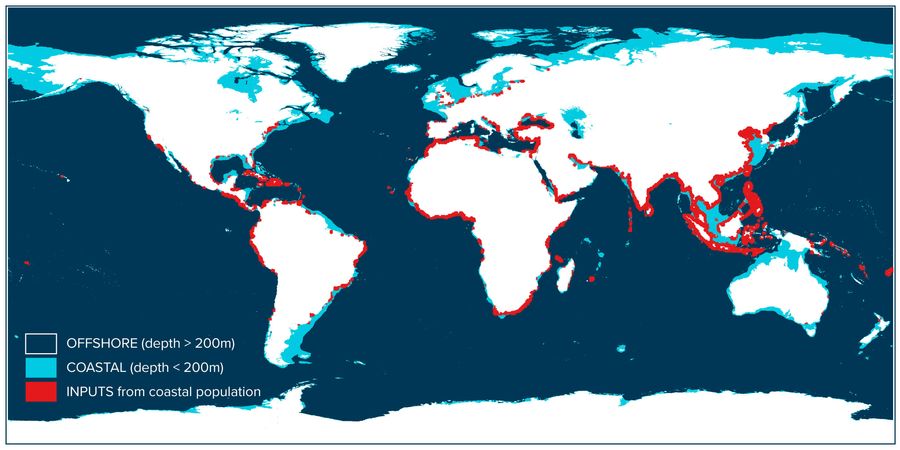

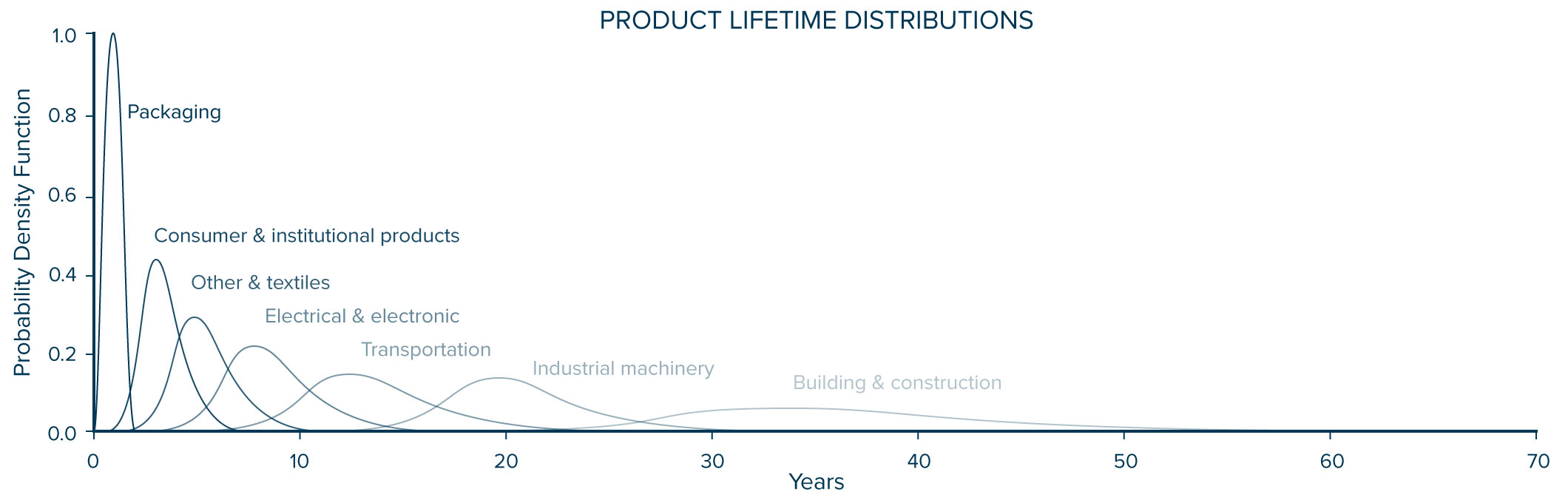

Every year from 1950 (when plastic was introduced to our societies), a fraction of plastic litter of various age groups has been released into coastal waters. These groups represent global plastic production, use, and discard by different market sectors (figure below), in the form of macro-sized (greater than 0.5 cm) buoyant polymers (HDPE, LDPE, PP, 57.3% of global plastic production).

Once introduced into coastal waters, a fraction of plastic litter is transported to offshore waters and another settles or strands on landmasses in coastal environments. The remaining plastic litter stays in coastal waters. Finally, as time passes, a fraction of the mass of macroplastics (referenced in our three model boxes) degrades into microplastics, leaving our model domain. The process is repeated every year from 1950 to now.

This model has obvious limitations, due to its simplicity, but it can be a useful tool to determine the key processes governing the dispersion of floating plastic for the entire ocean. Based on the age population of plastic reported from the Mega Expedition in 2015, we estimated a whole-ocean degradation rate of floating macroplastics to not exceed 3% per year, as opposed to more than 90%, as previously proposed by some scientists.

Due to a low degradation rate, our model suggests that the capture mechanisms around the shoreline must play an important role in removing plastic from the surface of the ocean. This assumption was validated by the analysis of trajectories of over a million model particles representing the dispersion of floating plastic at sea. When released into significant coastal hotspots for ocean plastic emissions, we observed that after a year around 97% of all the particles that were released would have spent at least two consecutive days in proximity to a shoreline, substantially increasing their chance of stranding.

With this model, including low degradation and high stranding rates, we show that the age of plastic between coastal waters and offshore ocean waters is very different: younger plastic less than five years old is more likely to be found in coastal waters and predominantly older plastic is floating in offshore accumulation areas. This agrees well with field observations which report a majority of identifiable objects in coastal waters and a majority of unidentified plastic fragments in offshore gyres. The idea that only certain types of plastic accumulate in the GPGP was one of the main conclusions of our 2018 publication.

These considerations of age of plastic population and the implication of delay between source and accumulation zones are important for understanding the future state of the oceans. In this study, we argue that floating plastic pollution forming oceanic garbage patches is highly persistent. If left alone, our models predict that this material may remain at the surface of the ocean for several decades, if not centuries.