Why We Must Clean The Ocean Garbage Patches

Back to updatesAt The Ocean Cleanup, our mission is to rid the world’s oceans of plastic. To achieve this, our strategy is two-pronged: remove it from rivers and waterways that flow into the ocean, and extract legacy debris from the ocean.

In my last blog I explained why we focus on intercepting plastic in rivers; we think it is the fastest and most cost-effective way to stop the inflow of plastic to the oceans. (If you haven’t read the post yet, I recommend doing so before reading ahead.)

However, we think it is equally essential to clean up the legacy pollution that has accumulated in the oceans.

When someone learns about ocean plastic pollution, the most common initial response we hear is, “Let’s just hire some ships and go clean it up!” Those who spend slightly more time delving into the issue usually come to realize that the oceans are very big, and that it would probably be much easier to find ways to prevent plastic from entering the ocean in the first place, versus cleaning it up at sea. We’ve studied the issue for years, yet here we are, working to clean up plastic directly from the oceans.

Why? Let me explain.

THE PROBLEM IN A NUTSHELL

Every year about a million tons of plastic pollution enter the world’s oceans. Most of it comes from rivers. Of this plastic, the majority only stays afloat in the ocean for a brief period of time.

Because about half of this plastic floats, a substantial amount of trash quickly sinks into the sediment. According to our modelling, within one month, more than 80% of what remains afloat has the potential to beach on a coastline not far from where it entered the ocean. And within one year, 97% might end up back on land. At this point, only a tiny fraction of plastic emissions appears to be ‘lucky’ enough to escape the grip of coastlines and make it to the open ocean. However, once the plastic finds itself in the open ocean, we can expect it to stay there for a very long time.

Plastic accumulates in five areas in the world’s oceans, known as the subtropical oceanic gyres. Basically, these are vast circular currents that trap the floating trash inside of them. This is where the five ocean garbage patches can be found.

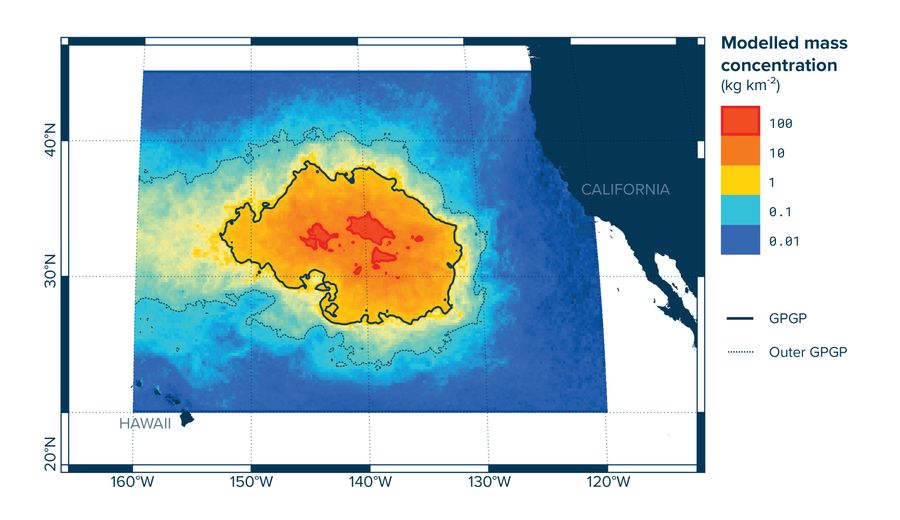

The ocean garbage patches are the planetary equivalent of the corner of your room to which you swept all the mess you left on the floor. The most polluted – and best-studied – of these is the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) located between Hawaii and California. The GPGP only covers about 0.5% of the world’s ocean surface, yet is estimated to contain more than 50% of all the plastic mass floating in the open oceans.

The word ‘patch’ is a bit of a misnomer, though. These accumulation zones are not islands of tightly packed trash, as they are sometimes portrayed in news reports. If only this were the case – cleanup would be so much easier! Instead, the trash is spread out over vast areas. In the GPGP, the average density of plastic is roughly the weight of one soccer ball for every soccer field worth of ocean; not exactly close to something you can walk on.

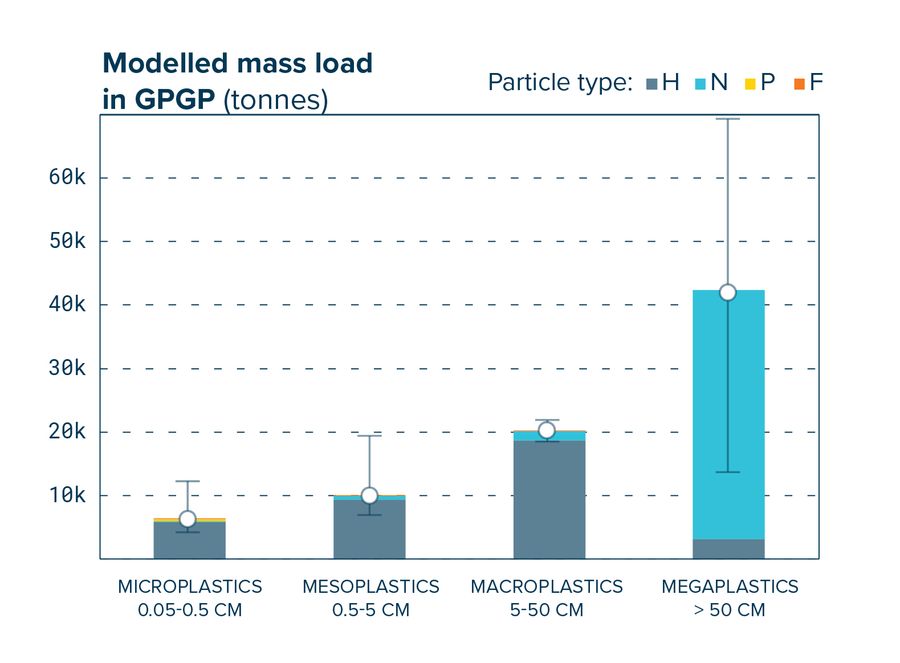

However, because these patches cover such a large area (the GPGP spans a piece of the ocean larger than France, Germany, and Spain combined), all these ‘soccer fields’ add up to vast amounts of pollution. The GPGP now contains an estimated 100,000,000 kilograms of plastic. Associated with this plastic are all the well-known impacts of plastic pollution on ecosystems, human health, and economies. In fact, nowhere else is the ratio between plastic and naturally occurring prey as high as in the ocean garbage patches, ingestion risk for marine life (as well as the associated chemical effects) are likely highest here.

Still, you may rightly ask: why should we bother with cleaning up these areas if, pound for pound, it’s bound to be cheaper and easier to collect trash in river mouths? Wouldn’t it be enough to cut the source, as is the case for smog, for example? And why start with it now, rather than wait for the inflow to be solved first?

To answer these questions, it is vital to understand two things:

1. Plastic in the ocean garbage patches is highly persistent

2. Floating plastic becomes more harmful over time

A PERSISTENT PROBLEM

In short: we can only return to clean oceans if we clean up the ocean garbage patches. Stopping the source will prevent more plastic from entering the oceans. But the only way to reduce the amount of plastic across the ocean is to actually go out there and clean it up.

The reason for this is that plastic pollution is persistent. Imagine the condition/scenario of a bathtub that is overflowing. For a nonpersistent pollutant scenario, merely closing the tap is enough to solve the problem. But in the case of a persistent pollutant, one also has to mop up the overflow on the floor.

This is why Londoners today don’t suffer anymore from the soot emitted during the Great Smog of 1952. Yet, it’s still unhealthy to consume fish from the San Francisco Bay due to PCBs emitted in that same year. Soot is not a persistent pollutant, while PCBs are. It’s why smog problems in wealthy countries have reduced considerably since the 1970s and why plastic pollution isn’t like smog.

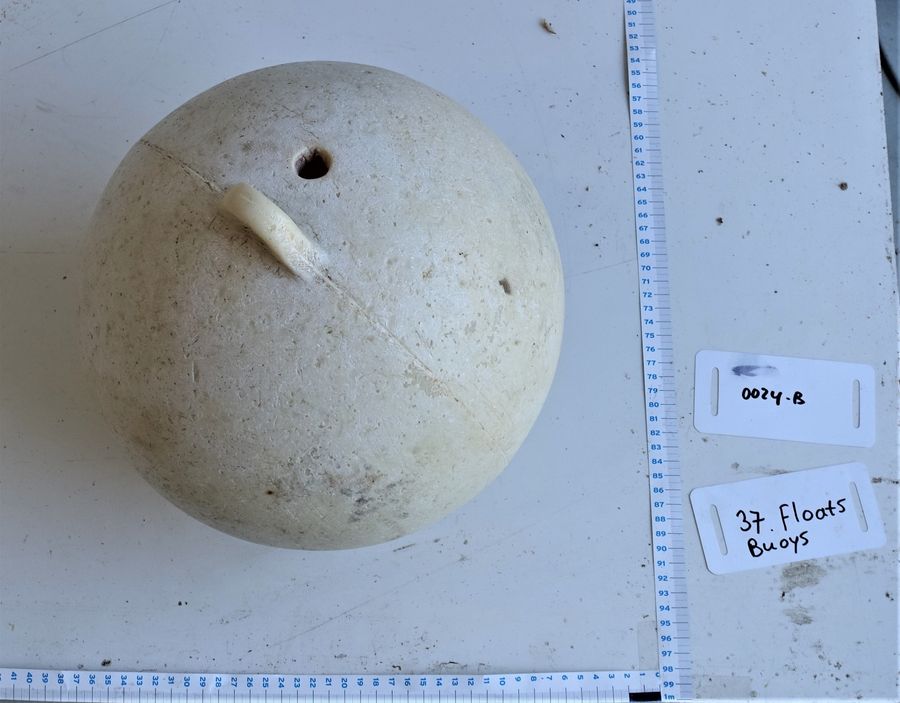

Plastics are incredibly stable and durable. This is good if you want to make lasting products (or fake diamonds), but it’s problematic if it ends up in the environment. During our most recent expedition to the GPGP, the oldest object we found with its production date still identifiable was a buoy from 1966.

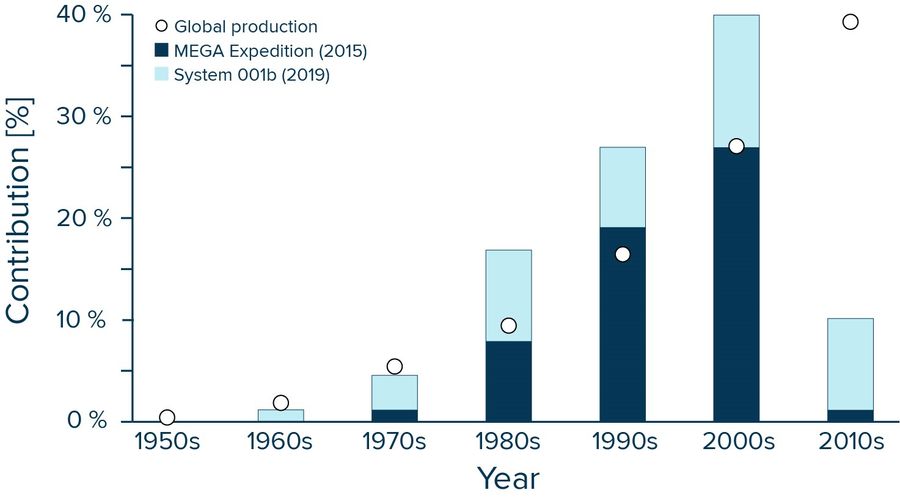

Might this observation have been a fluke? An object that was stored indoors for decades and only recently entered the oceans? Probably not. Our researchers have analyzed many dozens of recovered objects from which we could identify the production date. Suppose the old items we find are exceptions. In that case, we’d expect those older objects to be exceptions in our catch, between a bulk of more recently produced objects. Instead, we find that the age distribution of plastic in the patch neatly overlaps with the plastic production trends of the last 60 years. About half of the plastic we could identify has a production date from the 1990s or earlier. These findings are a strong indication that all this plastic has been gradually accumulating in the patches and does not leave.

Recent lab experiments support this conclusion. A Dutch team recreated the ocean environment in the lab and measured the degradation of various plastic objects over time. They found that the weight loss of plastic items typically observed at sea is less than 1% per year. Other experiments used strong UV lamps to accelerate the degradation process, which indicated that polyethylene (the most common type of plastic in the ocean) might take “up to centuries” to fully degrade.

Besides degradation, plastic can leave the patch if it gets spewed onto a coastline. This, however, also seems to be a rare occurrence. The only shorelines close to the patches are remote islands. For example, under 100 tons of trash is estimated to escape the GPGP and wash up on the Hawaiian Islands every year. This is an impressive amount, but it is only 0.1% of the mass of the whole GPGP.

Clearly, these ocean garbage patches are not going away by themselves in any reasonable frame of time.

A TICKING TIME BOMB

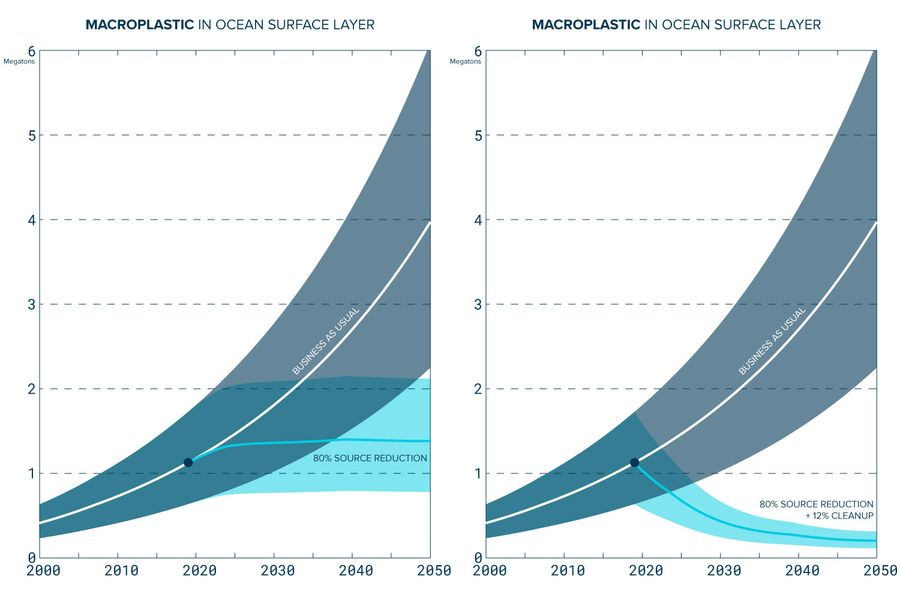

A lot of plastic is still entering the oceans every day. And if I could choose, I’d prefer to catch a piece of plastic before it enters the ocean than wait for it to have accumulated in the middle of the ocean. So why not just focus on closing the tap now, and worry about cleaning up the patches later, once the plastic inflow has been halted?

The obvious answer to this is that the sooner the patches have been cleaned up, the sooner they stop causing harm. Less obvious is the fact that the longer we wait, the more harmful the accumulated plastic becomes. While the true degradation of plastic into harmless compounds is predicted to take centuries, the sun and waves do break down the objects into smaller and smaller pieces over time. For example, a single crate will ultimately turn into hundreds of thousands of microplastic particles. Every piece of plastic has the potential to cause damage, so the higher the plastic count, the greater risk of harm the plastic might pose to the oceans.

At the moment, about 5-10% of the plastic mass in the GPGP is microplastic. On the one hand, this is good news; it means most plastic hasn’t fragmented into microplastics yet. But it also means that the number of microplastics might increase by a factor of 10 or more if we don’t remove the plastic floating in the oceans today. The longer we wait with the cleanup, the more microplastics there will be in the oceans.

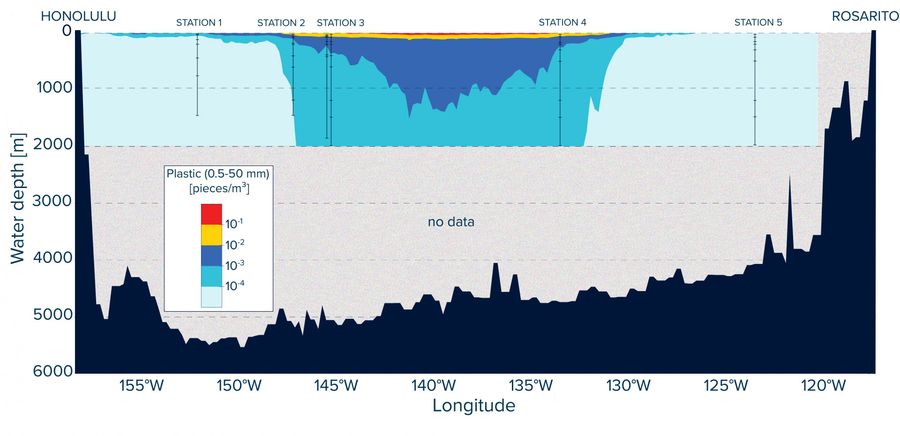

What’s more, plastic doesn’t only become more harmful over time, it also becomes harder to clean up. The smaller the pieces become, the less buoyant they are. In 2019, our researchers crossed the GPGP and took measurements from the surface down to 2000 meters of depth. Under the patch, we found that it was snowing microplastics. The concentrations of this fallout are tens of thousands of times lower than those we see at the surface. The amount of microplastics we found suspended in the deep sea represents less than 10% of the total mass of plastic in the patch. Still, if we don’t remove the surface plastic, we may expect that eventually most of this other 90% will also end up under the surface.

This is a crucial point. By cleaning up the surface waters of the ocean garbage patches now, we can prevent a 2D problem from becoming a 3D problem. At this moment, most plastic is in the upper two meters of the ocean. If this plastic disperses throughout the top 2000 meters, the volume of water we would need to clean increases a thousandfold. In other words, the effort required to clean a vertically dispersed patch would be like cleaning up today’s ocean garbage patches a thousand times! So we have a brief window of opportunity to take care of the legacy plastic before it turns into microplastics and pollutes the entire water column for an indefinite duration.

From this perspective, one might argue that cleanup is prevention too. By removing the floating trash now, we prevent this trash from doing further harm and becoming almost impossible to eradicate.

A NECESSARY INGREDIENT

If I could choose, I’d rather catch plastic with Interceptors in rivers than with ocean cleanup systems. Unfortunately, it’s too late for the hundreds of millions of kilos of trash that already pollute the ocean today. Stopping plastic before it reaches the oceans allows us to keep the amount of plastic in the oceans constant, but the only way to reduce the amount of ocean plastic is to clean up that legacy pollution. That’s what we need to do to truly rid the oceans of plastic.

The good news: if we stop plastic from entering the ocean, most of the ocean cleans itself.

The bad news: this does not apply to the ocean garbage patches.

This is why we need to clean them up https://t.co/5TcKWuFnUs pic.twitter.com/dcxf09HXP6

— Boyan Slat (@BoyanSlat) September 17, 2021

One can debate what the optimal resource allocation is between different removal activities. I agree with those who argue that the majority of resources aimed at solving plastic pollution should now go to stopping the inflow. Yet, that doesn’t mean we should only do one or the other. Humanity works on eradicating diseases, solving climate change, reducing poverty, and improving education in parallel. Clearly, humanity can do more than one thing at the same time.

Returning to the analogy of the overflowing bathtub: here, an optimal strategy might be for a few people to work on trying to close the tap, while one person starts to mop the floor.

You see this parallel approach after an oil spill; some workers attempt to stop the leak, while in parallel, others try to clean up the pollution that has already been leaked to prevent further harm to the ecosystem. Similarly, the prevention and cleanup of ocean plastic can, and should, be applied in tandem.

Cleaning the ocean garbage patches will not be easy. System 002 is currently undergoing testing in the GPGP, and first results look promising. Still, success is not guaranteed. Even if System 002 proves its effectiveness in the next few weeks, there is still a complex journey ahead to scale it up.

All I know is that it’s worth trying.