Persistent legacy plastic fragments are rising disproportionally faster than larger floating objects in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Back to updatesLatest peer-reviewed publication reveals that legacy plastic fragments are rising disproportionally faster than larger floating objects in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

At The Ocean Cleanup, our mission is to rid the world’s oceans of plastic. When drifting offshore, floating plastic pollution accumulates in areas where oceanic currents converge. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is the largest accumulation of floating ocean plastics in the world, home to an estimated 100,000 tons of plastic debris in an area twice the size of Texas.

As the only organization operating at scale in this region, we have a unique opportunity to address both the immediate crisis of plastic pollution and the need for crucial scientific data collection.

Cleanup operations are not only essential for reducing the vast accumulation of plastics in the ocean, but they also provide us with a unique platform to gather valuable data in remote regions like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch — data that would be difficult to obtain otherwise.

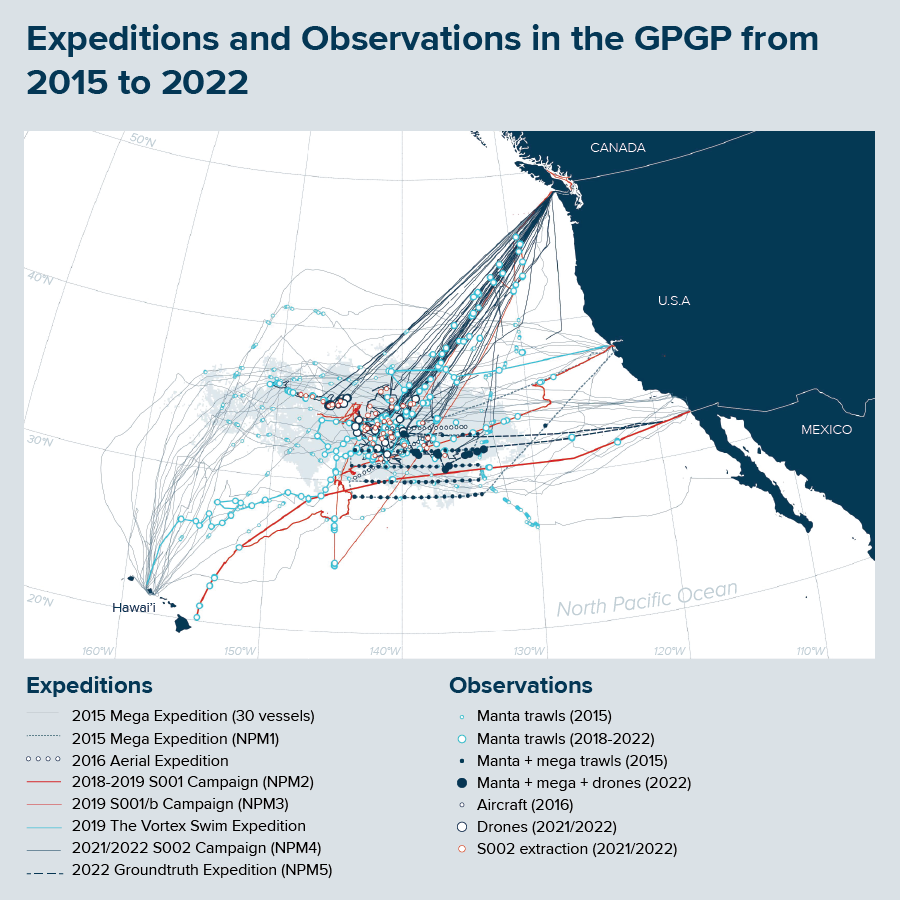

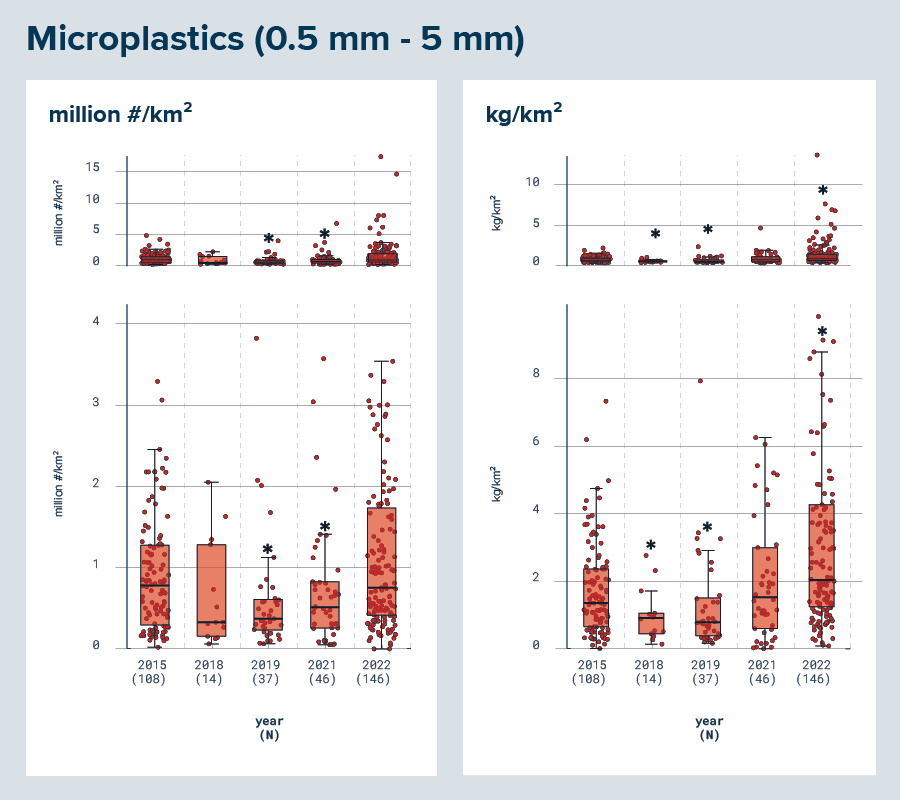

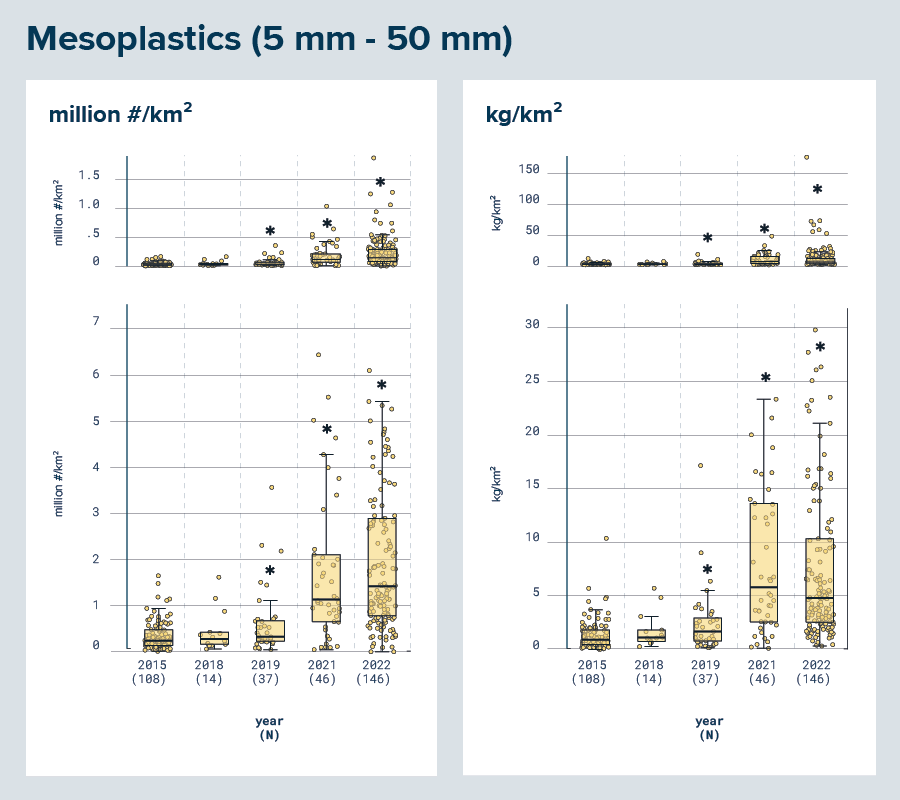

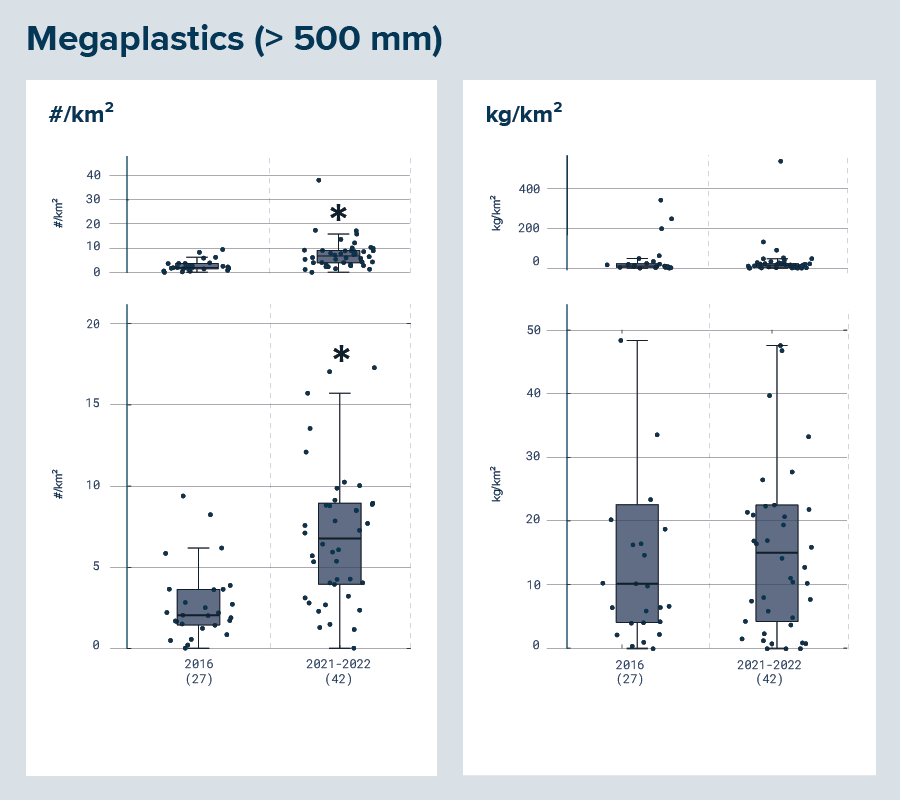

Over the past seven years, thanks to our offshore operations, we’ve been able to systematically monitor the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, collecting data through trawling nets, aerial imagery, and our cleanup system itself. These efforts have enabled us to build an extensive dataset that has revealed an alarming trend: the rapid rise in smaller plastic fragments (0.5–50 mm).

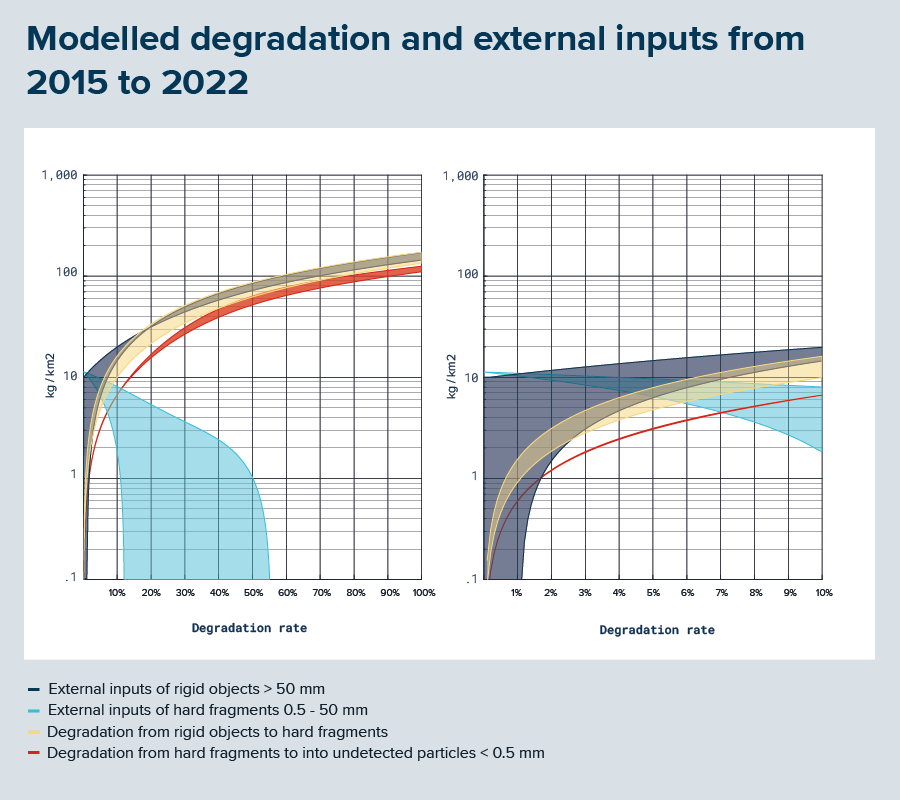

Our findings show that the concentration of smaller plastic fragments has skyrocketed—from 2.9 kg per square kilometer in 2015 to 14.2 kg per square kilometer in 2022. This nearly fivefold increase in just seven years highlights the urgency of the situation.

The rise in plastic fragments is deeply concerning, not only because they are harder to collect than larger debris but because they pose significant risks to marine life and ecosystems. Plastic pollution damages ecosystems, with over 900 species affected by plastic pollution and more than 100 species threatened with extinction in part due to it. Microplastics can be ingested by marine species, disrupting food chains, and they also affect the global carbon cycle. This widespread and lasting harm could last hundreds of years.

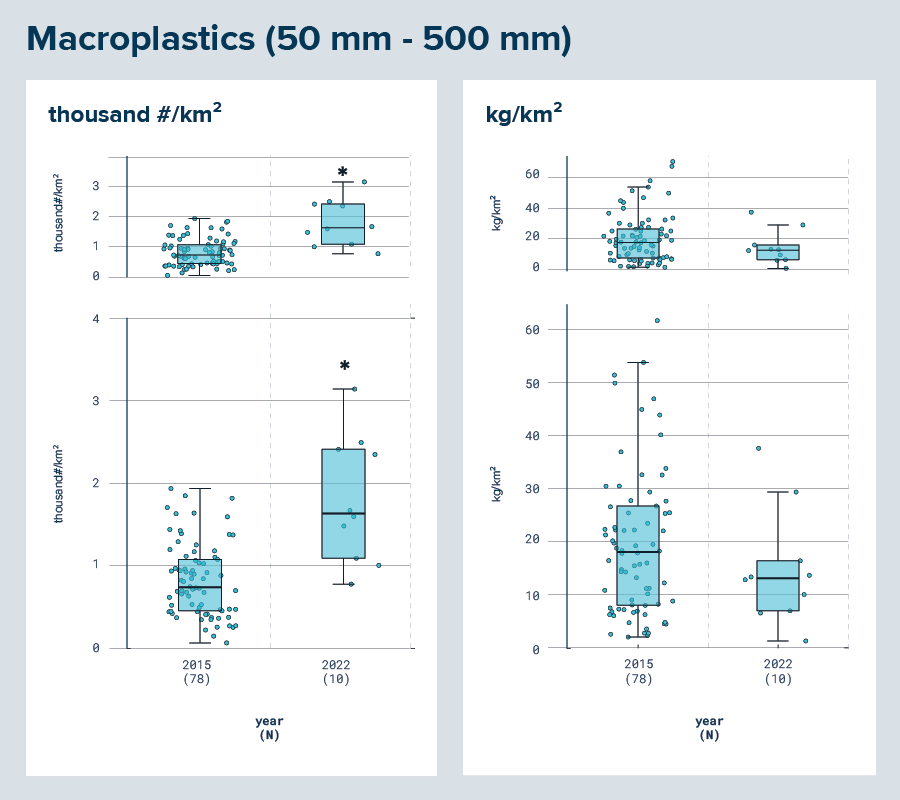

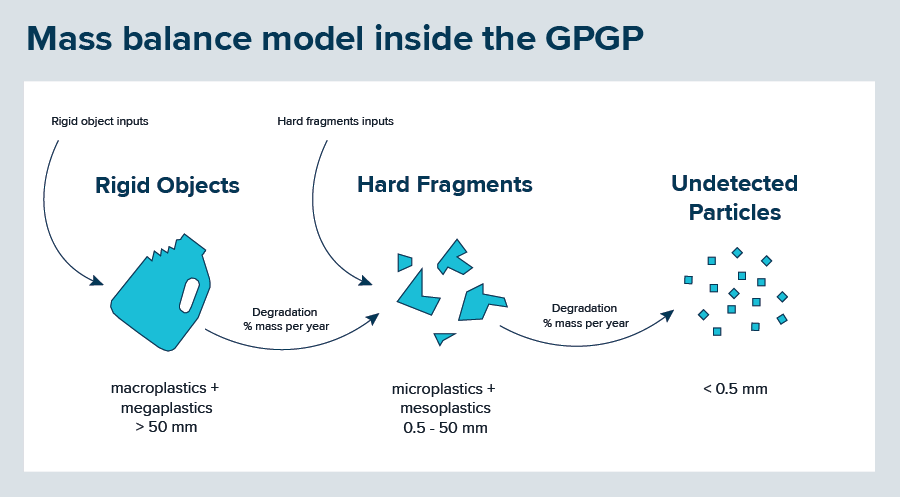

What’s more, our research indicates that most of this smaller plastic material isn’t simply the result of larger debris breaking down inside the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Instead, by establishing a simple mass balance model for the region, findings indicate it is likely new foreign material originating from the degradation of legacy pollution accumulated in the world’s rivers and coastlines in the past decades. Eventually, it accumulates in the ocean at a faster rate than previously anticipated, signaling that we are still far from controlling the influx of waste.

These findings highlight the persistent nature of floating plastic pollution: much of the plastic already present in the ocean remains afloat for years or even decades. The significant rise in plastic fragments observed between 2015 and 2022 points to the enduring presence of plastics, which resist natural degradation and continue to accumulate in ocean gyres like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This persistence means that once plastics enter the marine environment, they can circulate and accumulate for an extended duration, causing long-term harm to marine ecosystems and wildlife.

This research reinforces the urgent need for a comprehensive, full life cycle approach to tackle plastic pollution. To truly address the problem, we must simultaneously control plastic production, improve waste management infrastructure, stop ongoing leakage, and eliminate accumulated legacy plastic waste.

Remediation is more than just cleaning up plastic. It is a key tool for gathering the data needed to truly understand the scale and nature of ocean plastic pollution. Insights that are essential for effective policies addressing the problem. By consistently collecting and analyzing this data, we can track trends, identify sources, and measure the effectiveness of interventions. Such data helps formulate strategies, better inform policymakers and contribute to global efforts for a healthy ocean, including in the context of achieving SDG Goal 14 and the UN Ocean Decade of Science for Sustainable Development and specifically the UN Treaty on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) as well as the UN Global Plastics Treaty. And monitoring does not only inform, it also ensures accountability across parties.

The urgency can’t be overstated. The rapid increase in plastic fragments creates long-term, potentially irreversible damage to our oceans. Cleanup operations are not just about responding to the current problem; they’re a proactive approach to understanding the deeper issues and finding long-term solutions.

Cleanup activities need to be scaled up across other regions of the world to not only remove plastic waste from the environment but also provide a global framework for monitoring and combating this crisis. If we delay, the impacts of plastic pollution will become even more challenging to reverse.